A collector's view

Global art and creation open to all in the art of the 60s-70s: from the delegation of the making of an artwork in favor of a knowing public to the transfer of artistic initiative to a public of creators.

Artists asking other people to carry out their artwork have been subject to recent interest. This was brought to the forefront by Randy Kennedy's article entitled Tricky business of authenticity published in the International New York Times (Saturday-Sunday 21-22 December 2013). The article refers to the presence of damaged or poorly made works of art by Judd, Flavin and Morris in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum, works previously in the Panza di Biumo collection. Randy Kennedy writes: “Judd was among a wave of postwar artists to introduce the idea of industrial fabrication — the removal of the artist’s hand — to the conception of art. And most of his best-known geometric objects, in plywood, metal and other materials, were made by specialty craftsmen. But this hands-off delegation, far from distancing him from the work, seemed only to deepen his control, one of many facts that Panza, who died in 2010, failed to grasp, Judd said.” The delegation here appears to be based on thorough technical requirements, which were wrongly observed by the collector. But the carpenters relied on for completion of the work did not yet use in 68-70 in Europe, as in the United States, Panza being Italian, materials as trivial as plywood, hence design errors in manufacturing. And the question, at first purely technical, led into a study of knowledge and customs. It may not be due to monetary concerns as suggested by Judd but rather out of carelessness that Panza failed to comply, as he adapted to the idea of creation open to collectors, the public and other artists, such as suggested by the works of art in the exhibition. This is the heart of the subject; art now belongs to the public. This delegation is endless: as part of a chain in Broodthaers, permanent in Filliou, super-temporal in Isou and Sabatier, perpetual and for all, pertaining to the domain of public freehold, in the case of Isou, Filliou and Weiner. Would Panza have succumbed to the intoxication born out of the possibility of an unlimited creation open to all? We shall partake to this exhilaration of creation as either actors, embarked artists, or accomplices observing multiple experiments proposed around the idea of creative delegation in the 60s-70s.

The artists displayed in the exhibition are contemporaneous with minimal artists, they belong to other movements such as Conceptual art, Fluxus and Lettrism. They are: Art & Language, George Brecht, Marcel Broodthaers, Robert Filliou, Gérard Gasiorowski, Isidore Isou, Nam June Paik, Roland Sabatier, Daniel Spoerri and Lawrence Weiner.

This exhibition is part of

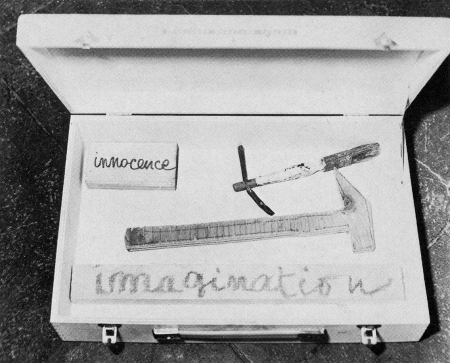

Robert Filliou, The Permanent Creation Tool Box 1969.

De Robert Filliou, son compagnonnage avec Brecht, Broodthaers et Spoerri a été décrit dans le § 1. Artistes hors les lignes communes d’une époque, mais c’est pour mieux accomplir leurs singuliers «travaux», ces délégations le montrent. L’important et l’importance, Filliou les déplacent, son conseil doit être écouté de chacun et l’abréviation de sa posture pour saisir l’enjeu sera la bienvenue : « Qu’on vous souhaite bonne chance me semble plus important que de regarder une peinture moderne » et dans ce même texte, Filliou de s’abréger : « Je suis en quelque sorte l’artiste des artistes. »

A l’intérieur de cette Box, un outil rudimentaire par sa fabrication, une de ses extrémités se termine en pinceau, l’autre d’un marteau. Innocence et Imagination se lisent sur deux morceaux de bois.

Cette boîte pourrait sembler s’apparenter à l’étagère supertemporelle d’Isidore Isou du § 7 et fournir deux outils nécessaires à la production d’œuvres : un pinceau et un marteau ; elle en diffère immédiatement par sa différence, ici nul « mode d’emploi », ni procédure ni avertissement et délégation serait trop vite dit.

Dans cette boîte, néanmoins, une double convocation, celle de l’imagination, « la fée du logis » disait l’âge classique, fée parce que seule, elle peut présenter n’importe quel existant, puisqu’elle est la faculté de la représentation, pas de mimésis sans elle. Mais on le sait, l’imagination est enchaînée au réel existant, elle le re-présente une seconde fois, son éloignement du réel n’est pas même imaginable, - le monstre composite, l’hippogriffe de Descartes est encore re-présentation, assemblage fait à l’image d’éléments existants ; quant à l’imagination comme faculté d’abstraction, elle n’est même pas « imaginée » par une esthétique de la hauteur de celle de Hegel.

A l’imagination, Robert Filliou assigne une tâche tout autre qu’il désigne par l’autrisme, sa posture artistique de production qui rend possible la création permanente :

« Je parle beaucoup de la création permanente1 et j’essaie de la rendre accessible aux autres….il y a quelque chose que j’estime être le secret relatif à la création permanente c’est ce qui suit : Quoique tu fasses, fais autre chose. En Français, cela s’appelle l’Autrisme. Comme je ne supporte pas les ismes, j’en fais un par ironie. » ( Catalogue Hanovre, Arc 2, Berne,1984 p.20 ). A cet autrisme, doit être joint le principe d’équivalence : « Qu’une œuvre soit bien faite, mal faite ou pas faite ? me semble du point de vue de la création permanente indifférent. » Bien que Filliou ait pu dans certains de ces énoncés, donner sa préférence au « mal fait », jusqu’à l’élever en sa spécialité : « Ma spécialité est le Mal Fait. »

Ce principe d’équivalence n’a rien d’une quelconque provocation, il tient en ceci et c’est son « secret » : « Chaque fois que vous pensez, pensez à autre chose. Quoi que vous fassiez, faites autre chose. Le secret de la création permanente est de ne rien désirer, ne rien choisir, pleinement conscient, pleinement éveillé ; tranquillement assis, sans rien faire. » Dans ces trois riens, celui du non choix, du non désir et du non faire, une ouverture au bouddhisme Zen, celui rappelé au § 3 de son ami et compagnon d’expériences artistiques George Brecht. Alors c’est l’innocence du devenir, du tout Zen qui se profile, sur ce point, le §11.

Filliou n’a jamais ouvert cette boîte par une quelconque délégation, mais dans ses textes et notations, c’est la création permanente qui devient objet de partage et de participation étendue au plus grand monde. Ainsi en hiver 1963, à Paris, prenant le métro pour visiter son ami l’architecte Joachim Pfeufer, Filliou note, à propos de la création permanente, elle est : « ce que je dois partager, avec tout le monde, elle est basée sur la joie, l’humour, le dépaysement, la bonne volonté et la participation » et donc une délégation a maxima.